Why we shouldn’t de-clutter our family history

De-cluttering may be the road to an easier life but be sure you’re not losing important family history says Bryher Scudamore. She has riveting tales from her forebears to prove the point.

The fashion for minimalist living is growing apace and the latest book on the benefits of de-cluttering (“Stuffocation” by James Wallman) has just been published to much acclaim. But before you rush to join the de-cluttering club I have a cautionary tale.

The worst thing I ever did was destroy my love letters. It was years ago and I had been happily married for about 15 years. We were moving and I was busy de-cluttering and so I burned the love letters I’d had from my teenage boyfriends. Before I destroyed them I read them one last time and they brought back so many memories and powerful emotions. The joys of juvenile love and the agony of having been dumped all came flooding back.

Now I have been happily married – to the same husband – for 39 years and how I wish I hadn’t destroyed those letters. Why? Because I am writing my life story and there are so many gaps in my youth. My memory has never been brilliant and without the evidence I can hardly remember anything about those times. It set me to thinking about how dangerous de-cluttering can be.

Hoarding, minimalism and right-sizing

The popular UK Channel 4 television series which links up people obsessed with cleaning with hoarders is big on getting rid of clutter – and rightfully so. It is not only unhealthy, it is also dangerous. And that’s particularly the case for older people.

As we get older we seem to acquire not only our own clutter but that of our deceased parents and grandparents. And I find it so difficult to throw away something that has no value but is priceless for its memories.

Yet while I will never live a minimalist life, like so many of my age – 64 – I desperately need to get rid of much of the stuff I have collected over the years.

A visit from an organisation such as right-size.co.uk who can carefully and sympathetically reduce clutter might be the answer. But not every company is as good and so beware of what gets thrown away.

An example of what I think is “destructive de-cluttering” was a television series years ago called “Life Laundry”. A hoarder was told to throw out a delightful sketch made by her father of her 21st birthday party seating plan. I remember shouting at the TV “Don’t throw that out, it is a precious part of your life story”. But it went into the bin.

More recently some priceless historic photographs of the building of Tower Bridge were de-cluttered and thrown into a skip. Thank goodness someone spotted them and retrieved them. They are now valuable documentary evidence about the construction of this iconic building. We would be a lot poorer in our understanding of that feat of engineering without those images.

Not many people would have such historically valuable photographs in their cupboards but most people have photographs and documents – maybe a diary of a grandparent or great-grandparent.

Letters tell my great grandfather’s story

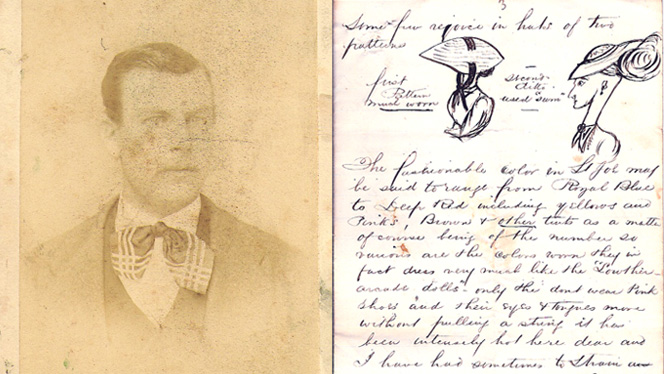

I am particularly grateful to my grandfather and father because neither of them de-cluttered some precious letters – at least they are precious to me – written by my great grandfather, Walter Mitchell. At 23 he went to America to seek his fortune. His letters to his sweetheart Emillie Read (whom he later married) and his mother and brother are full of stories of his adventures.

I found them in a de-cluttering phase after my father had died and was clearing out his “junk”. I read the 14 letters great-grandfather sent home with fascination.

Walter had sailed in June 1867 from London on a ship called the Hudson and arrived in New York and then travelled by train from New York to Indiana and then on to Missouri, working as a carpenter, and then spending three months hunting on the prairies. He writes about “a monstrous snow storm” and describes how they reached St Joseph, Missouri, at the very end of the railway.

Saint Joseph was where 20 years later the notorious outlaw Jesse James was killed. “Some days after our arrival,” he writes still in that elegant handwriting, “a quantity of red Indians (peaceable tribe) the Mowhawk we were informed had pitched their wigwams on the shores of Kansas territory, and being very anxious to see (them) we paddled our own canoe to the shore of Kansas across the Missouri river with much bother and sundry little mishaps made our canoe fast to a tree and introduced ourselves to the real live injun, being surrounded by a heap of warriors, squaws and their papousees (children).”

Did Walter make his fortune in America, become a Carnegie or a Rockefeller? Sadly, no. After four years of hard work and sacrifice he came back without even a plot of land or a log cabin to his name.

I came across a letter to the sweetheart he had left behind, Emilie, my great-grandmother which explained why.

Firstly, he could only get a grant of land if he agreed to swear allegiance to the brand new nation, and he refused to “take an oath to fight if necessary against Dear old England and its Queen” Victoria. Secondly, a close friend, Tom, had gone down with typhoid fever, and for three months my great-grandfather looked after him, “without a trade and penniless”. And thirdly, he constantly longed for Emilie, “sometimes when waiting for a letter I read and reread your old ones until I almost know them by heart”. So he came home to her.

So in 1870 he sailed back to Liverpool. And did well. He married Emilie, became a clerk of works for some big and important projects in London, and died on February 20, 1898 aged just 53.

How I wished I had met this brave, loyal, hard-working young man, only 23 years old when he took this extraordinary leap in the dark, across the Atlantic.

Then, another glorious moment, in an old leather bound photograph album full of anonymous Victorian relatives I found his picture, uncaptioned, unidentified, apart from the name of the photographer, George Adams, in Worcester, Massachusetts. So I knew this young man with a sweet face and an elegant cravat was the great-grandfather I never knew I had.

De-clutter stuff but don’t throw away memories

Of course, Walter Mitchell’s story will have pride of place in the book of my own life, my autodotbiography. But what if someone had de-cluttered him? I would never have known of his adventures and I would have been the poorer for not knowing about my ancestor. Thank goodness my grandfather and then my father, who had the letters and family photographs handed down to them, didn’t de-clutter.

And it may be that I have a little of his character running through my genes because I too have risked everything on my own adventure. At the age of 60 I started a business called autodotbiography.com, in the hope that life stories and precious family photographs can be saved for posterity and provide families with an heirloom.

So by all means throw away “things”, but don’t throw away your family memories. They cannot be replaced and once gone, are gone forever.

If you’d like to write your own family story, visit autodotbiography.com for more details.

You may like to read these articles:

How to make downsizing a good experience

10 questions to ask before it’s too late – especially the 10th

What do you do when saving stuff seems to have become hoarding?

If you’ve enjoyed this article why not receive updates of our latest articles through our free newsletter? Simply join the family by clicking the box below.